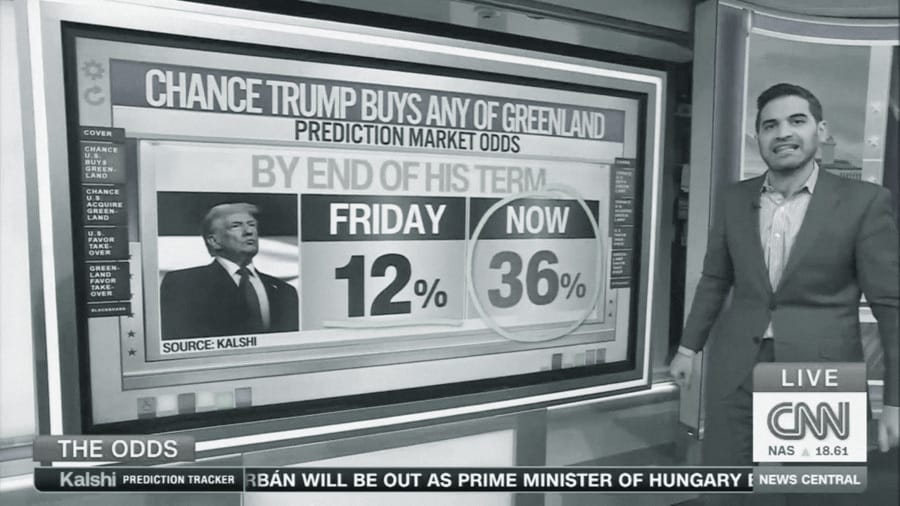

Kalshi prediction market odds of Donald Trump buying Greenland are presented on CNN. (Screen grab via Snapstream/CNN)

Did you hear this week that Amazon billionaire Jeff Bezos advised Gen Z entrepreneurs to start their careers at real-world jobs like McDonald’s or Palantir before launching a business?

Or that the Justice Department under Donald Trump was charging Don Lemon under the Ku Klux Klan Act for allegedly inciting a church raid in Minnesota?

Or that the U.S. and Denmark had quietly established a working group for “technical talks” around Trump’s foolish attempt to take Greenland?

None of it was true.

All three claims circulated widely on social media after being promoted by Polymarket and Kalshi—two gambling websites that refer to themselves as “prediction markets.” They are just a sampling of the false or misleading claims posted by platforms now taking billions of dollars in wagers on virtually any conceivable news or sports outcome.

“Nope,” Bezos wrote Thursday in response to the post attributing the comments to him. “Not sure why Polymarket made this up.”

It would be easy to dismiss this kind of misinformation as junk content from modern-day bookies trying to lure the gullible into placing a bet. But these pay-to-play platforms have become deeply embedded in the mainstream media ecosystem—gaining legitimacy and reach through partnerships with legacy outlets.

In recent months, CNN and CNBC have both struck deals with Kalshi to feature its betting odds as part of their coverage, similar to how networks incorporate polling data or economic indicators into segments. Dow Jones, the parent company of The Wall Street Journal, Barron’s, and MarketWatch, has partnered with Polymarket, with chief executive Almar Latour lauding its supposed value as “a rapidly growing source of real-time insight into collective beliefs about future events.”

Even the Jay Penske-owned Golden Globes joined in, integrating Polymarket betting data into this month’s broadcast with live on-screen odds predicting award winners—what Polymarket founder Shayne Coplan described as “the single most mainstream prediction market integration to date.”

But unlike public opinion polls—which, for all their flaws, rely on scientific sampling and transparent methodologies—prediction markets are not measures of broad sentiment or proxies for voter intention. At best, they reflect the behavior of a narrow group of people motivated enough to wager money. At their worst, they are ripe for manipulation by political operatives or foreign actors with both the means and the incentive to move gambling lines in their favor.

Notably, most news organizations did not include prediction market odds in their coverage prior to striking what are likely lucrative deals with companies like Kalshi and Polymarket. That suggests they did not actually find the data to be very informative for viewers prior to inking fruitful agreements.

Indeed, it appears that legacy media companies are pursuing these partnerships less out of editorial conviction than financial necessity. As advertising revenues continue to erode and the linear television business declines, outlets like CNN and CNBC are under mounting pressure to identify new, nontraditional revenue streams. The terms of the partnerships between Kalshi and CNN and CNBC weren't publicly disclosed, but money is changing hands in both deals, Business Insider’s James Faris reported.

“We believe in data as a strong complement to the news,” Kalshi spokesperson Elisabeth Diana told Status in a statement. “Sometimes (rarely) when moving fast, we rely on sources that aren’t accurate. There is a stark difference between getting, say, three posts wrong out of the hundreds we put out, versus blatantly and chaotically making up news for ‘fun.’” A Polymarket spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

But as prediction market data is woven into mainstream news coverage, it normalizes the act of gambling itself. When respected outlets repeatedly showcase betting odds, they implicitly legitimize wagering, risking pulling more people into gambling behavior. Recent studies have found a surge of gambling addition in the wake of legalized sports betting.

And there’s other reason for concern. U.S. intelligence agencies have long warned about foreign efforts to influence American public opinion. Imagine a scenario in which a well-funded actor quietly funnels millions in crypto into a prediction market to spike the odds of Trump’s attempted Greenland takeover—only to have a major cable network report that movement as a meaningful signal. The effect could create a feedback loop: money moves the market, the market is credibly reported by news outlets, and the news moves public perception—and potentially reality itself.

“Prediction markets offer just one source of data that journalists can use in telling a story,” a CNN spokesperson told Status. “When used, it complements other reporting and data sources, such as polling. It is not a replacement for other sources and has no impact on editorial judgment.”

News organizations have long been criticized for obsessing over the political “horse race”—who’s up and who’s down—at the expense of substantive reporting on issues that actually affect people’s lives. Prediction markets threaten to supercharge that tendency, offering a constant drip of price fluctuations that look authoritative but often mean very little. Audiences already skeptical of polls may struggle to distinguish speculative trading prices from legitimate survey data.

“Polymarket + X = the internet’s ultimate truth machine,” the company absurdly boasted on Elon Musk’s platform.

The fact that political gambling exists is not a reason itself for news organizations to legitimize it in coverage. Prediction markets may be entertaining and even lucrative ventures but they are not journalism. And the more news outlets pretend otherwise, the more they risk becoming part of the casino themselves.